Traveling around the world to try new foods, or gathering with loved ones to feast during celebrations and holidays, are just a few examples of how deeply enjoyable and culturally meaningful eating can be. However, for millions of people living with dysphagia, a condition that causes difficulty swallowing, eating requires much more effort and constant vigilance to stay safe.1

Understanding the Risks

People with dysphagia often struggle to move food or liquid safely from the mouth to the stomach. Sometimes, food and liquid can enter the airway instead, leading to aspiration and potentially life-threatening complications such as pneumonia.2,3,5 The underlying causes for dysphagia vary widely. Neurological conditions, such as stroke, can leave lasting impairments to muscular coordination needed for swallowing, while structural conditions such as head and neck cancer can disrupt the anatomy required for safe swallowing.1,5,6

Aspiration pneumonia is one of the most serious risks associated with dysphagia. When food, liquid, or saliva accidentally enters the lungs instead of the stomach, it can cause a severe infection. This condition is one of the leading causes of hospitalization and death among older adults—yet it can be preventable with early detection and proper swallowing care.

The IDDSI Framework: A Standardized Approach

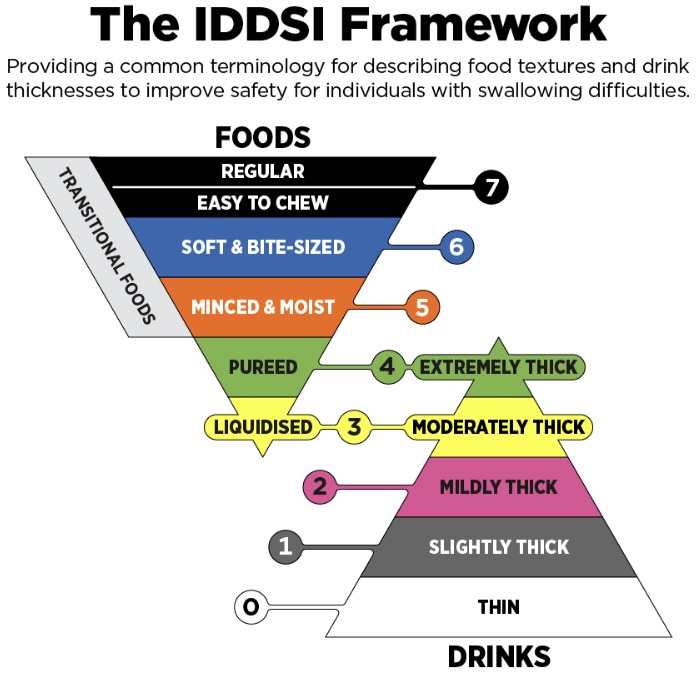

Despite the varied causes of dysphagia, many individuals share a common need for modified food textures and specialized diets tailored to their unique swallowing abilities. The International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative (IDDSI) provides a clear framework for this need, offering standardized terminology for texture and thickness levels that supports communication between healthcare professionals, patients, and caregivers.4

The IDDSI Framework provides standardized levels for food textures and liquid thickness, helping ensure safe swallowing for individuals with dysphagia.

Pureed foods, minced-and-moist textures, and thickened liquids are just a few examples of IDDSI-aligned modifications designed to reduce the risk of choking or aspiration. More broadly, these modifications not only enhance safety but also help ensure that individuals with dysphagia can participate in the shared joy of eating.

The Financial Burden of Safe Eating

Unfortunately, these essential items are also some of the most costly purchases for many. For instance, ready-to-eat purees, thickened liquids, and soft-textured meals are frequently priced higher than standard foods, placing a significant financial strain on those who rely on them daily. Further, for families already burdened by medical bills and disability-related expenses, or those living on very limited incomes, these added costs can render safe eating inaccessible.

Beyond Financial Barriers

For others, this barrier goes beyond finances. Many people are unaware that everyday recipes can be adapted to meet specific swallowing needs. Many others may not know how to modify textures safely while still preserving taste and nutritional value. Learning to puree, blend, thicken, or reshape foods safely takes practice and education, which not everyone has access to.

Clearly, the complexity of managing dysphagia extends well beyond the swallow itself. As we celebrate the holiday season, it becomes even more important to ensure that everyone can enjoy the foods they love and experience a shared culture of connection.

No one should have to sit on the sidelines of a holiday meal. By bringing awareness to these realities, we empower ourselves and our communities to better support individuals living with dysphagia with genuine empathy, a vital step toward a more inclusive society.

References

- Martino, R., Foley, N., Bhogal, S., Diamant, N., Speechley, M., & Teasell, R. (2005). Dysphagia after stroke: Incidence, diagnosis, and pulmonary complications. Stroke, 36(12), 2756–2763.

- Langmore, S. E., Skarupski, K. A., Park, P. S., & Fries, B. E. (2002). Predictors of aspiration pneumonia in nursing home residents. Dysphagia, 17(4), 298–307.

- Marik, P. E., & Kaplan, D. (2003). Aspiration pneumonia and dysphagia in the elderly. Chest, 124(1), 328–336.

- International Dysphagia Diet Standardisation Initiative (IDDSI). (2019). IDDSI Framework. Retrieved from https://iddsi.org

- Hutcheson, K. A., & Lewin, J. S. (2013). Functional outcomes after chemoradiotherapy for head and neck cancer: Dysphagia and rehabilitation. Current Oncology Reports, 15(2), 162–169.

- Bath, P. M., & Lee, H. S. (2018). Neurogenic dysphagia: Prevalence and pathophysiology. International Journal of Stroke, 13(1), 3–10.